Image credit Katheryn Owens

Project Overview

In 2023 we completed our PhD. The thesis used performance writing to understand and illustrate aspects of millennial experience, with specific interest in precarious housing and labour. It drew on an understanding of millennial precarity that references Lauren Berlants analysis of the requirements to experience ‘a good life’. The experience of precarity in these aspects of millennial life means that even within our privileged positions we share a feeling of ‘living on the edge’ (Ahmed, 2017: 238), which in turn prevents us from being able to imagine alternatives to our situation. We developed an expanded definition of performance writing that included forms it might take and methods by which it might be devised. Performance writing is presented as a hopeful strategy that may not offer an alternative future or a way through this, but offers potential through its relationship to making. The research is particularly interested in DIY approaches and as such is concerned with non hierarchical or institutionally authorised forms of art.

Performance writing is understood as being text that is performance and performance that is text with no fixed boundaries between terms as opposed to (for example) writing for performance (such as scripts). Performance writing considers its visual, physical, aural, and performative elements. In our practice it may take the form of scores, instructions, maps, walking, knitting, zines, and audio recordings.

We drew on Barthes’ literary theories of readerly and writerly text, which is integral to our assertion that performance writing undergoes a continuous process of rewriting through its encounter, and this is significant in how we frame making (and re-making) performance texts. Additionally, the thesis also contributed new ways of doing ‘friendship as method’ (see Tillman-Healy, 2003) within academic research. As a research duo, we are still concerned with friendship, collaborative strategies, hope and performance writing.

Going forward, we are interested in how performance writing might articulate experiences of the body, and how it might share embodied understandings. Performance writing is uniquely placed to do this because of its potential to be rewritten and altered through its encounter. As such, we are looking towards leisure and the body as both a means of generating writing, and as indicative of wider social and political concerns, using swimming as a research tool.

Swimming, as an embodied practice, requires you to submerge all (or part) of your body into water. It feels both natural and at the same time requires a level of skill and learning. Whilst the act of swimming can be explained and theorised, it is learnt through doing and known through bodily experience. There are many ways to swim, paddle, splash, dip, kick in the water which means it can be accessible to everyone, depending on the body of water. Swimming can also be a therapeutic exercise; the body feels differently underwater and can help people move in ways they are not able to outside of the water (see Tonic of the Sea, Maggs 2019). Swimming is also a social act that has been depicted through art histories in relation to queer desire through images of groups of men bathing or of paintings of men swimming in pools (Boaden, 2024).

Swimming pools also serve an important part of community and the right to leisure activities connects to work and labour. Swimming is also a practice of self-care; a way to relax, cool-down, distress. Being in water is an important part of ritual and sacred histories, and swimming also offers a way to keep fit and healthy. There is, however, also a dangerous side to swimming, as if you are not able to swim properly and the water is too deep or too rough then this can lead to death. There are also dark sides to swimming, particularly in relation to the sea where many people have risked their lives to cross borders and escape harm. Swimming can be a matter of survival, and the history of the sea (especially the Atlantic) is entangled with colonialism (Hameed, 2016).

Currently the project is in its early stages and we are refining its research objectives. Current intentions include:

To investigate the relationship between art, labour, and post-work theory through the activity of swimming. We will develop a set of interdisciplinary contemporary artistic outputs spanning the fields of performance, sound, text-based and sculpture/object making. How can we develop art through a practice of swimming?

To develop a new body of artistic research that uses the concept of post-work to examine art and labour.

To analyse the relationship between the body, thinking and writing and to consider these as caring practices.

To consider the challenges in ‘writing’ embodied experience, and to further develop understandings of performance writing as having potential to do this.

To analyse the importance of repeated association in this process: for example, returning to swimming sites, repeated actions of swimming, and swimming as a collaborative experience as expanding ones embodied understandings. Drawing on Deleuze (1994), repetition aids in deepening understandings and revealing differences, changed states and unfixed positions; such as the swimmers relationship to site and an audience’s unfixed interpretation of performance writing .

‘Care’ here is rooted in decentering commodified modes of care. The project draws on narratives of care such as James Thompson’s Care Aesthetics (2022) and The Care Lab (ongoing) which describes care as ‘an artful practice. Moments of care (…) demonstrate embodied, sensory and practical skills’ (thecarelab.org.uk/projects). This project draws on intersectional narratives and benefits from feminist, Black, Queer and Disability studies, particularly in terms of non hierarchical collective acts, the politics of leisure in relation to labour, and modes of providing self care. For example, Simone Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic (2014), spanned healthcare, performance and holistic practice to centre Black experience, specifically the overlooked care labour of Black women. Tricia Hersey’s The Nap Ministry (ongoing) uses the mantra ‘Rest is Resistance’ to explore the politics of refusal through rest, in response to trauma and the marginalisation of Black women (thenapministry.wordpress.com/). Rebecca Tadman’s writing on Queer performance highlights the ways ‘cultural production’ is often undervalued in the face of more profitable forms of labour, and the complexity of performing labour collectivity that relies on individuals contributing time, often unpaid. In light of this, radical care is an ‘active practice’ that seeks ‘mutual thriving’ (2023: 78).

Swimming will be used here as a strategy for thinking and generating writing. Walking has a history of being used in this way in relation to performance, writing and psychogeography, and the project will utilise some of this history (see Mock, 2009) (Smith, 2015). There is less written about a psychogeographical approach to swimming, though examples of swimming and performance include Amy Sharrocks SWIM (2007) in which participants travelled across London by swimming in public pools and ponds, inspired by John Cheever’s 1964 story The Swimmer, and Laura Hope’s Crazywell (2017) a participatory performance reenacting local mythology. Contemporary academic research about outdoor swimming includes the geography PhD project Swimdemere by Taylor Butler-Eldridge which looks at the motivations for open water swimming. Sports science research includes ethnographic studies into the social aspects of swimming (see Moles, 2020).

Performance writing and swimming share temporal qualities. The former makes explicit the cognitive process between thinking and creation, where writing is a form of thinking, but also where the making of objects that house the performance writing have temporal, durational qualities. Swimming shares these qualities; it is an activity that places us in a landscape (whether at the pool or wild swimming) and that is simultaneously a mode of travel (you move through the water) and a mode of repetition – of strokes, of laps – that usually puts you back at your starting point. Like a derive (a wander without a destination), swimming can be a deeply sensory moment of thinking time. It can be both intensely physical, and restful. It can be about the activity or about the culture around it (for example, spending time in the sauna or chatting to friends). Significantly, swimming is a useful example of embodied knowledge; whilst we can explain to one another the mechanics of swimming, it is through doing it that we learn.

The project uses a practice as research methodology that draws on reflexive strategies. This uses both an autoethnographic approach (where the researchers experiences are considered within the analysis of the research) to generate performance writing (using bodily experience as an iterative generative tool), in conjunction with a senses based ethnography (which considers knowledge gained through smell, taste, touch, sound, sight and how we experience the world). The autoethnography is in conjunction with participatory and interview based activities, allowing insights into other swimmers’ sensory experiences. The research considers both swimming and writing, as well as knowledge production, as inherently collaborative activities that are informed by environment, memory, access, shared and individual narrative histories. Performance writing here will be used to consider the challenges in writing embodied knowledge, where often ‘the multi-sensory dimensions of social life are suppressed or transformed in the making of texts’ (Sparkes, 2009: 33).

The initial phase of the research places specific emphasis on the following: the body at leisure and performing labour, swimming as a psychogeographical approach that offers a way of understanding the environment. Swimming as a collaborative act between self, environment, other swimmers and water users, as well as the cultural and mythological histories of swimming sites. This stage will refine the thematic concerns and locate the work within specific sites.

Identifying Sites

We are initially looking at 3 sites, beginning with Mermaids Pool (details below). The other two sites are Padley Gorge and Withington Baths.

Padley Gorge:

Katheryn: The OS map shows on the moor above Padley Gorge a stone circle. Every time I went hiking there I would look for it to no avail. It was marked in a field overgrown with ferns and I figured the map was showing the site of where the circle was rather than the remains. Anyway, one time I was walking with Callums friends and I went to look for the circle again, as it had become a tradition. It was too early in the year for the ferns to the field so it was much easier to walk through and we stopped where I thought it would be and stood on a small stone. Callums friend stood on a small stone to the right of me and another of his friends stood on a small stone to to the left and i looked at our feet and the shape of our bodies and realised we were stood on the stone circle! The small stones continued round in a large loop, now exposed. Where I had been expecting large standing stones or the remains of standing stones there were instead smallish rocks secured in the ground.

Padley Gorge can be accessed from Grindleford Train Station and is an ancient woodland (and a temperate rainforest) with a series of streams (the Burbage Brook) and pools. Historically, the Burbage Brook as the boundary marker between Derbyshire and Yorkshire. The gorge opens up on to moorland with huge rock formations so it feels like you are walking through two different landscapes. Some of the fallen trees are studded with coins which people have hammered on over decades for luck.

Withington Baths:

Opened 1st May 1913, in 1914 it became the 1st public baths in Manchester to allow mixed swimming.

Since 2015 the pool has been owned by a community led organisation (Love Withington Baths) which saved it from closure. Unfortunately Chorlton Baths could not be saved, closing in 2015 and now looking likely it will be redeveloped into homes despite ongoing attempts by the Friends of Chortlon Baths to return it to public use. Similarly Levenshulme Baths closed despite public protests.

http://www.lovewithingtonbaths.com/about: ‘The community galvanised and joined together in non-political, family-friendly protests and held a march through the streets, signing a petition to Save The Baths and gathering an unprecedented 8000 signatures in just two weeks. We presented this to Sir Richard Leese, City Council Leader, on Valentine’s Day 2013’ .

The building was designed by Henry Price (1867-1944), a City Council architect, who also designed Withington Public Library. The style of the Baths combines elements of Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts movement.

There were originally plans for a third pool which was never built and by the 1990s, council cuts meant Pool 1 was drained and boarded over, creating a new gym for community use. Pool 2 has continued to be well used by school, for lessons, by gym users and local swimmers.

On New Year’s Eve, 1940, during the Second World War, an air raid shelter directly in front of the baths took a direct hit and seven ARP wardens lost their lives.

In the early years of the 1930s, local swimmer Cecelia Wolstenholme trained at Withington Baths for the Olympic Games. At this time, Cecelia and her sister Beatrice were two of the most dominant female swimmers in Britain. Cecelia represented Great Britain during the 1930s in the Olympics, the European Championships and England

Katheryn: One of my memories is from when I first moved to Manchester. I went swimming semi regularly and got chatting to people in the sauna. I remember speaking to someone who was very hungover who had also just moved to the area, he had got drunk at a work social and was trying to sweat the hangover out. Another time there was a group in the sauna and it was pretty crowded. They were all chatting and seemed to know each other and it seemed an unlikely bunch of people to be friends and I can’t remember if I asked or if they just introduced themselves and explained their situation to me, but they had met in the sauna at Chorlton Baths, getting to know each other just through seeing the same people repeatedly there. When that closed they looked for somewhere else to go, and at first tried the new pool on Princess Parkway, but they didn’t like it (I think the cost, the more corporate / clinical feel, can’t just turn up etc). So they started using Withington Baths, and now they are a group of mates who host barbeques for one another. I had just moved from London where I had felt lonely and isolated and being in the sauna that day really made me joyful and hopeful.

Another thing I love about Withington Baths is the ladies night. Now, in many ways ladies night is quite annoying for actually trying to swim. It is crowded and can be really noisy and overstimulating. And I don’t personally feel any less comfortable if I am swimming on a mixed night. Ladies night is for 2 hours on a Wednesday night only. But it is so so so brilliant because It allows people go to swim who can’t swim on mixed nights for cultural or religious reasons. It allows people to go and swim who feel anxious or uncomfortable and feel safer on ladies night (as far as I am aware, it is not cis women only, though I could be wrong). The result is, the pool is used by people who are completely covered and by people in really tiny bikinis all at the same time and I know in theory the pool could be used by people dressed this way anytime but in practice it doesn’t work that way, and I love that there’s a night where it doesn’t matter and it is a really playful fun evening.

Now Withington Baths is somewhere I go for exercise but also to catch up with friends; there are a few of us who sometimes will go swimming together (though really it ends up being more chatting and practicing handstands). One time we tried a water aerobics class which was really fun because it is mainly just playing. We were the youngest there.

Mermaids Pool

Details!

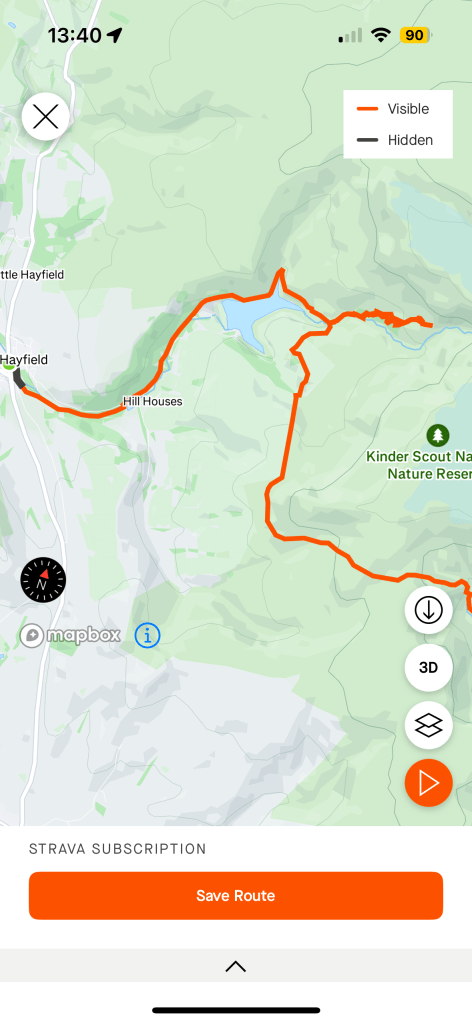

Katheryn: I first became interested in Mermaids Pool when I went on a hike with a friend and we got lost and I was anxious because I had set the route and my friend was not bothered at all that we were lost because she said we’d figure it out eventually. This was so reassuring in more ways than one and the day was a really good adventure. At some point we saw a pool in the distance and said we should look for it again some day. Later I googled it and found it was called Mermaids Pool. The group chat we are in (for arranging swimming) is called ‘mermaids’, and this felt like too good a coincidence. In reality, I have probably seen that pool before that day, because I hike there often. But any memory I have of that has been firmly replaced by that day. Since then, I have hiked past it quite a bit and the last time tried to look for a route down, with the intention of going there next time. It’s quite hard to get to I think, but I recently got a book on wild swims in the Peak District, and a route down is featured in the book. I realised I am not stable footed to hike down to it, so I plotted a route from Hayfield, walking up from the reservoir, off the official path and following sheep tracks to reach the water. I can imagine before the towns were here people walking from Mam Tor, along Rushups Edge and down to the water to perform water rituals.

Mermaids Pool is a small tarn situated between Kinder Reservoir and Kinder Scout, below Kinder Downfall, in the Peak District. There is loads of cool mythology and history up there:

The Aetherius Society: This group (cult) were led by George KIng, and still exist today. In the 1950s, in London, George King was contacted by an alien called Aetherius and the very very short version is that by communicating with and observing the aliens we can achieve peace on earth. Now based in LA, the society believes that (amongst other beliefs) certain mountains worldwide that have special spiritual properties with which we can contact the aliens. As such, members take part in pilgrimages to these holy sites. One of which is Kinder Scout. Each of the holy mountains has a ‘charged rock’ on it, daubed in white paint with GK. We’ve never been able to find it but we keep looking.

The Edale Cross is a medieval cross also acting as a boundary marker at the Kinder Low end of the plateau, not far from the top of Jacobs Ladder. It was probably put there in 1157 by Cistercean Monks but no one knows for sure.

If you turn left at the top of Jacobs ladder and walk across Brown Knoll to Rushups Edge to approach Mam Tor, you will pass The Lords Seat, an Iron Age burial mound (turn right instead of left to reach Kinder Downfall and Mermaids Pool. This is assuming you are approaching from Edale not Hayfield).

A popular wild swimming spot for hikers, Mermaids Pool is the home of a mermaid who appears visible once a year, on Easter Sunday. If you swim in the pool on that day you will be granted eternal life. Some believe that if the mermaid doesn’t take kindly to you, she will instead drag you under and kill you. Mermaids Pool was used for water worship rituals in Celtic times. The pool water is saline which seems odd given it is inland, but it is apparently connected underground directly to the atlantic.

From https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=28649

‘There are a number of local legends concerning the Mermaids Pool other than the water nymph conferring immortality on those she favoured or a watery death on those she didnt !!! The pool is said to be connected to the Atlantic by an underground tunnel that allows the nymph to travel to the ocean. Another legend concerns a witch, Suzannah Huggin, who lived in Hayfield in 1760. She was persuaded by an old sailor to buy a bewitching charm and from the moment she did many things went wrong in the village such a fevers, cattle disease and food going bad. The villagers found Suzannah and dragged her in front of the George Hotel where they pelted her with rocks and rotten food, and almost killed her. Someone from Tom Heys Farm took the charm from her but they didn’t keep it for long as the milk wouldn’t churn, the pigs wouldn’t eat and objects in the farm were thrown about. The vicar was called who agreed to perform an exorcism and after the ceremony the charm was said to have flown through the air and plunge into the Mermaids Pool where it remains to this day. The mermaid could possibly be a folk memory of the Celtic water Goddess Arnemetia who was worshipped in this area and attested to by the temple and springs at Buxton (Roman Aquae Arnematiae) and by a Roman altar from Brough. The Mermaids pool at Hayfield could well have been a rural place of worship for the Celtic and Romano-British of the area.’

Working Reference List

Ahmed, S. (2017) Living a Feminist Life, Duke University Press.

Berlant, L (2011) Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press.

Boocock, E (2024) ;Navigating grief: an autoethnographic tale of open water swimming and loss’, Leisure Studies. Pp 1-13. [Online] Available at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/02614367.2024.2302345?needAccess=true> (Accessed 6th November 2024).

Deleuze, G (1994) Difference and Repetition, Columbia University Press.

Mock, R (ed) Walking, Writing and Performance; Autobiographical Texts by Deirdre Heddon, Carl Lavery and Phil Smith, Intellect Ltd.

Moles, K (February 2021) ‘The Social World of Outdoor Swimming: Cultural Practices, Shared Meanings, and Bodily Encounters’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, Volume 45, Issue 1, pp 20 – 38.

The Nap Ministry (21/02/2022) ‘Rest is anything that connects your mind and body’, [Online]. Available at <https://thenapministry.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/rest-is-anything-that-connects-your-mind-and-body/> (Accessed 13th November 2024)

Smith, P (2015) Walking’s New Movement, Triarchy Press.

Sparkes, A (2009) ‘Ethnography and the senses: challenges and possibilities’, Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. Volume. 1, Number. 1, pp 21–35. [Online] Available at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/19398440802567923?needAccess=true> (Accessed 6th November 2024).

Tadman, R (2023) ‘Who Cares?: Ethics and Practices of Care and Making Change in Contemporary Queer Performance Production’, Contemporary Theatre Review, Volume 33 Nos 1-2, pp 61-79. [Online]. <Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10486801.2023.2173598> (Accessed 13th November 2024).

Thompson, J (2022) Care Aesthetics, Taylor and Francis.

Tillman-Healy, L. (2003) ‘Friendship as Method’, Qualitative Inquiry. Volume 9, Issue 5, pp 729 – 749. [Online] Available at <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/1077800403254894> (Accessed 17th August 2023).